Lightyears Collection

Harriet Hubbard Ayer

(1849-1903)

Click to enlarge Harriet Hubbard Ayer |

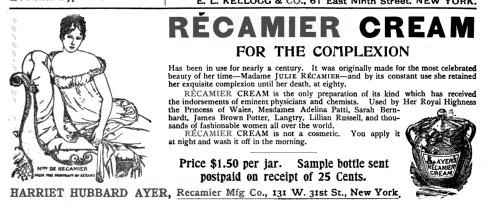

Harriet Hubbard Ayer never marketed a perfume. She build a successful, albeit short lived, business marketing cosmetic creams. The name of her business was Recamier Manufacturing Company. The name was that of a French beauty of the Napoleonic era. In Paris, Ayer had obtained a formula for a beauty cream said to have been specially prepared for this lady. Under Ayer's skillful management, it became her highly profitable Luxuria cream.

Only after the death of Harriet Hubbard Ayer was the company that still bears her name organized. This company, which still exists, has sold both a range of beauty products and perfume.

If ever a woman's life was beset by tragedy and triumphs it was that of Harriet Hubbard Ayer. Her biography is widely available, particularly in a book authored by her youngest daughter, Margaret Hubbard Ayer, "The Three Lives of Harriet Hubbard Ayer" (1957).

I first came across the name Harriet Hubbard Ayer in Lindy Woodhead's book, "War Paint" — a biography of Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden. Lindy told Ayer's tale in brief as an explanation of why Elizabeth Arden preferred to to have partners in her business — particularly male partners.

Click to enlarge Ad for Harriet Hubbard Ayer's Recamier Cream |

Ayer came from Chicago society but her father died while she was four and her mother became an invalid, apparently somewhat by choice. Harriet was educated at Sacred Heart Academy in Chicago and, at the age of 16, she married Herbert C. Ayer, son of a wealthy Chicago iron manufacturer.

In 1871 her second child died during the family's evacuation from their home during the Chicago fire. Herbert Ayer, said to be a drinker and womanizer, inherited his father's business but the business went smash. In 1883 Harriet separated from her husband, placed her two living daughters in boarding school, and moved to New York where she found employment as a salesperson with Syphers & Co., dealers in antique furniture. At ease in New York society, Ayer did well both for her employer and herself. She soon opened a shop of her own.

Among her clients was "Arizona Jim" — James Seymour — who proceeded to give her business advice and, it is said, encouraged her to start a cosmetics business. In 1886, after her divorce from Ayer had been finalized, she borrowed $50,000 from Seymour and organized the Recamier Manufacturing Company to sel her cosmetic cream. The business flourished and Seymour was repaid in full in a short time, though he later disputed this. Their business had been done on a handshake.

Ayer had become a personal object of interest to Seymour. She was not interested. Rebuffed, Seymour launched a aggressive campaign to make her life unpleasant.

Ayers, exhausted from business, divorce, and constant travel set out for Europe where daughter Margaret was studying piano. Seymour, it appears, made arrangements with both her daughter's piano teacher and her European physician to have her overdosed with narcotics. Ayer discovered the plot in time to save her life and her health.

Upon returning to New York, she discovered that Seymour had gained control of her company. Seymour had also encouraged an alliance between his son, Allen Lewis Seymour, and Ayer's eldest daughter, Hattie. In spite of Ayer's disapproval, in time they were wed. Seymour's efforts also succeeded for a while in alienating daughter Margaret from her mother.

Ayer sued to regain control of her business. Seymour charged that she had become drug addicted and erratic. Ayer charged that Seymour had used the drugs in a plot against her as well as stealing documents from a locked box in her home while she was in Europe. The New York Times and other city newspapers reported the lurid details. Ayer won the case and regained control of her business but her victory was short lived. Her business had been built on her impeccable reputation in society and this now was badly tarnished. Sales crashed.

But Seymour was not yet finished. Conspiring with Herbert Ayers, Harriet's ex-husband, and Hattie, now his daughter-in-law, the trio arranged to have Ayer involuntarily committed to an insane asylum in Bronxville, New York.

Ayer spent fourteen months isolated in the asylum, in solitary confinement, unable to send or receive letters, unable to receive fresh clothing. When her lawyers managed to free her — on a technicality, as the doctor who had signed the commitment papers was one day short of being licensed to do so — Ayer emerged from the asylum in the same dress and underclothes she had been wearing when she had entered, all now in tatters. Her red hair was now gray. She was forty pounds lighter.

Ayer hit the lecture trail with a presentation called "Fourteen Months in a Madhouse." It was a large success with the public.

In 1897 she obtained a post at the New York World writing a weekly beauty column. She took to journalism eagerly and expanded into regular reporting, including murders. But her focus was on women's topics.

In 1902 she published a hugely successful book, "Harriet Hubbard Ayer's Book of Health and Beauty." She died in 1903 from the flue.

Prior to her death she was reunited with both daughters. Additionally, she helped her ex-husband survive his declining years, saving him from abject poverty. Her younger daughter, Margaret, who had enjoyed a career as an actress, took over her mother's syndicated beauty column at the New York World. In 1913, Margaret married their editor, Frank Irving Cobb, who had become editor-in-chief of the World.

1907 — 1947

Click to enlarge Lillian Sefton, President, Harriet Hubbard Ayer, 1918-1947 |

Four years after the death of Harriet Hubbard Ayer, the Harriet Hubbard Ayer Corporation was organized. Rights to the name had been secured by Vincent Benjamin Thomas (1868-1918) who became the company's president. The launch had been affected with the assistance of several other gentlemen but within a short time, Thomas gained full control. He was assisted in the management of the company by his wife.

In 1905 Thomas had married Lillian Sefton of Washington, DC, a singer and actress. Sefton had appeared in at least one production with fellow actress, Margaret Hubbard Ayer, the younger daughter of Harriet Hubbard Ayer. It seems likely that this connection led to Benjamin's interest in cosmetics and his decision to obtain the Harriet Hubbard Ayer name. It is said that before taking the plunge, Benjamin had done considerable "due diligence" on the industry and had concluded that it offered opportunity.

Harriet Hubbard Ayer had never marketed perfume and her own views on the subject were ambiguous. Certain perfumes — heavier French perfumes — were, to her mind, suitable only for prostitutes and kept women. (In this view she was not so far from that of the pre-1920 views of Coco Chanel.)

Ayer did, however, find that lighter fragrances — Violets, for example — could be worn by decent women. This, in fact, was what the larger American fragrance houses — Colgate, California Perfume, and Watkins, for example — were offering.

Click on image to enlarge Rouge, showing Harriet Hubbard Ayer trademark. |

Click on image to enlarge

|

In 1907 when the Thomases entered the perfume and cosmetics business, the world was changing. Women were making freer use of cosmetics and perfume. This was the age of Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, Coty, and Richard Hudnut. The beauty business was on a roll.

Vincent B. Thomas died in 1918 at the age of 50 — younger than Harriet Hubbard Ayer at the time of her death. Several weeks after his death his wife was elected president and secretary of the company. In time she would become the highest paid female executive in America, earning a salary of $100,000 per year in 1937. (In 1930 she had paid the highest fine in history — $213,286 — for undervaluing a trunkful of clothes and jewelery she was bringing home from France.)

By 1925 Lillian Sefton Thomas had remarried, this time to American artist Robert Leftwich Dodge whose works appear at Vasser College and on the walls of the Library of Congress. Dodge now became art director for the company. He died in 1940.

In 1947, after negotiations with soon-to-be-architect-again Charles Luckman, 68-year-old Lillian Sefton Thomas Dodge sold Harriet Hubbard Ayer to Lever Brothers for $5,500,000, a low price in the eyes of analysts. The company had been grossing between $6 and $8 million annually.

1947 — PresentAfter the Lever Brothers purchase, Lillian Dodge was retained as an advisor. To run the company, Luckman hired Ralph P. Lewis away from Elizabeth Arden where he had been vice president and sales manager.

In spite of this auspicious new beginning, the high hopes were not recognized. Now, in addition to Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, Ayers had two new and very formidable competitors: Estee Lauder and Revlon.

Luckman left Lever Brothers in 1950 and returned to his first love — architecture. Through his new architectural partnership he piloted the construction of Madison Square Garden, Cape Canaveral and the Houston Space Center.

In 1953, Lever Brothers sold Harriet Hubbard Ayer and it was acquired by investors who have kept it alive in name. Minimal information on the current version of Harriet Hubbard Ayer can be found at the company's website: http://ayer-cosmetics.com

Perfumes by Harriete Hubbard Ayer

| Fragrance | Perfumer | Comments |

| Dear Heart (1920) | unknown | |

| Douces Fleurs (1922) | unknown | |

| Lilas (1922) | unknown | |

| Muguet (1922) | unknown | |

| Violette (1922) | unknown | |

| Apres Tout (1922) | unknown | |

| Mes Fleurs (1922) | unknown | |

| Prince Charming (1922) | unknown | |

| L'Ondee (1922) | unknown | |

| Papillon (1922) | unknown | |

| Doux Baiser (1922) | unknown | |

| Darling (1922) | unknown | |

| Ivresse D'Amour (1922) | unknown | |

| Brin D'Amour (1922) | unknown | |

| Harriet Hubbard Ayer (1937) | unknown | |

| Yu (1937) | unknown | |

| Pink Clover (1938) | unknown | |

| Tulip Time (1940) | unknown | |

| Honeysuckle (1943) | unknown | |

| Golden Hour (1945) | unknown | |

| Winter Carnival (1947) | unknown | |

| Golden Chance (1948) | unknown | |

| Pretty Package (1948) | unknown | |

| Golden Note (1948) | unknown | |

| Golden Splash (1948) | unknown | |

| Christmas Card (1951) | unknown | |

| Sweet William (1951) | unknown |

If you have any information to share with us about Harriet Hubbard Ayer, please use the the message sender below.

Would would Luckman have thought? For Christmas, 1953, working with Ideal Toy, the "new" Harriet Hubbard Ayer company introduced the Harriet Hubbard Ayer doll. Some would say this was an extention of doll purpose to introduce cosmetics and grooming. What a come down from bottles by J.Viard! |

Philip Goutell

Lightyears, Inc.